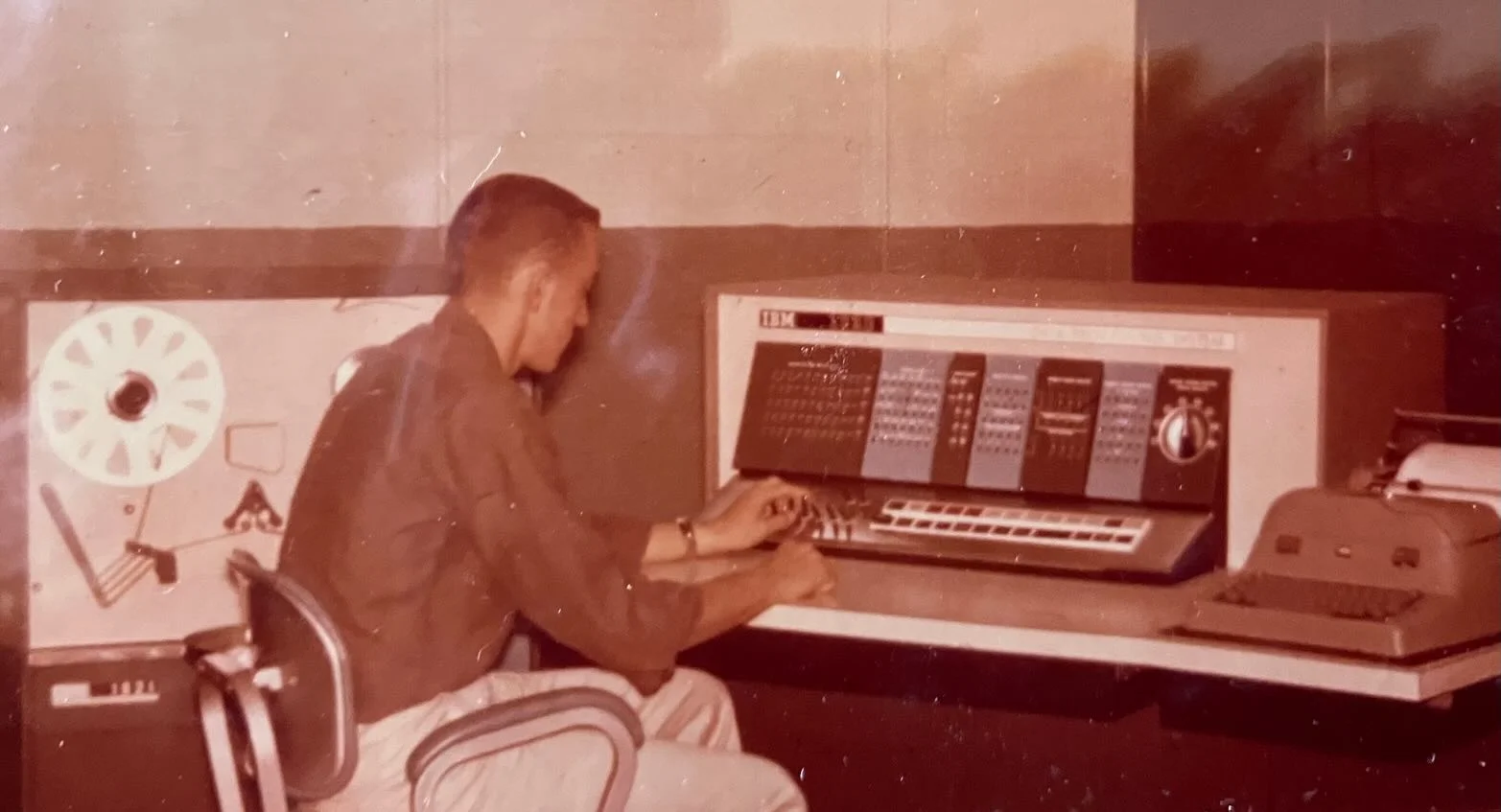

Back in the 1960’s I had a summer research job as an undergraduate at the University of Idaho assisting a member of the physics department with some numerical computations for color sites in crystals. The goal, as I remember it, was to determine their energy spectrum. To do this I had to learn some quantum mechanics, some numerical analysis, and some programming. In those days the latter meant Fortran, writing out the program by hand, punching it into a card deck, submitting the deck to a reader attached to an IBM 1620 computer, and then waiting for the output — usually a bug report — to appear on the line printer.

I learned a great deal that summer, flirted with physics for a while, and eventually went on to graduate school at Princeton in mathematics. A great cultural shock it was, but I survived and embarked on a long and satisfying career in mathematics.

Every few years I would get involved in some small programming project, occasionally as part of work, but usually just for fun or to satisfy my curiosity. Often in a different language than the one I used last time. Basic, Pascal, Lisp, Scheme, Javascript …

After I retired, I discovered a language family totally unbeknownst to me: typed functional programming and the languages Elm and Haskell. Such linguistic and conceptual beauty! I felt like Rip Van Winkle, having awakened after a long sleep to find a changed world.

I continue to work in this world, where I have found a wonderful community of generous and talented friends. My main effort is still directed to the development and improvement of scripta.io, a web app that provides on-line editor and publishing system for articles in mathematics, physics, and the like.

The app uses a markup language, Scripta, which has most of the functionality of LaTeX and much of the convenience of markdown.

Scripta documents can be exported to LaTeX and also to PDF. As you type text into the editor, it is immediately rendered. Thus you avoid the endless

write-compile-look-at-the-pdf-do-it-again-and-again loop. The design of the language also prevents many kinds of errors ab initio, e.g., it is impossible to not properly close an an enviroment

such as \begin{theorem} ... \end{theorem}.

Here is a small snippet of this language:

| theorem (Euclid)

There are infinitely many prime numbers

| theorem

There are infinitley many prime number $p \not\equiv 1 \text{ mod } 4$.

The Pythagorean formula reads $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$.

Know this formula for the test:

| equation

\int_0^1 x^n dx = \frac{1}{n+1}

| equation

a &= p + q \\

b &= p - q \\

r &= ab \\

&= (p + q)*(p - q)˚ \\

&= p^2 - q^2Here is the rendered text:

Theorem (Euclid). There are infinitely many prime numbers

Theorem. There are infinitley many prime number \(p \not\equiv 1 \text{ mod } 4\).

The Pythagorean formula reads \(a^2 + b^2 = c^2\).

Know this formula for the test:

\[ \int_0^1 x^n dx = \frac{1}{n+1} \]

\[ \begin{aligned} a &= p + q \\ b &= p - q \\ r &= ab \\ &= (p + q)*(p - q) \\ &= p^2 - q^2 \end{aligned} \]

I’ll discuss the Scripta markup language in a future post. A simplified version of it is used in this blog. Meanwhile, here is the current state of art: Scripta Test File.