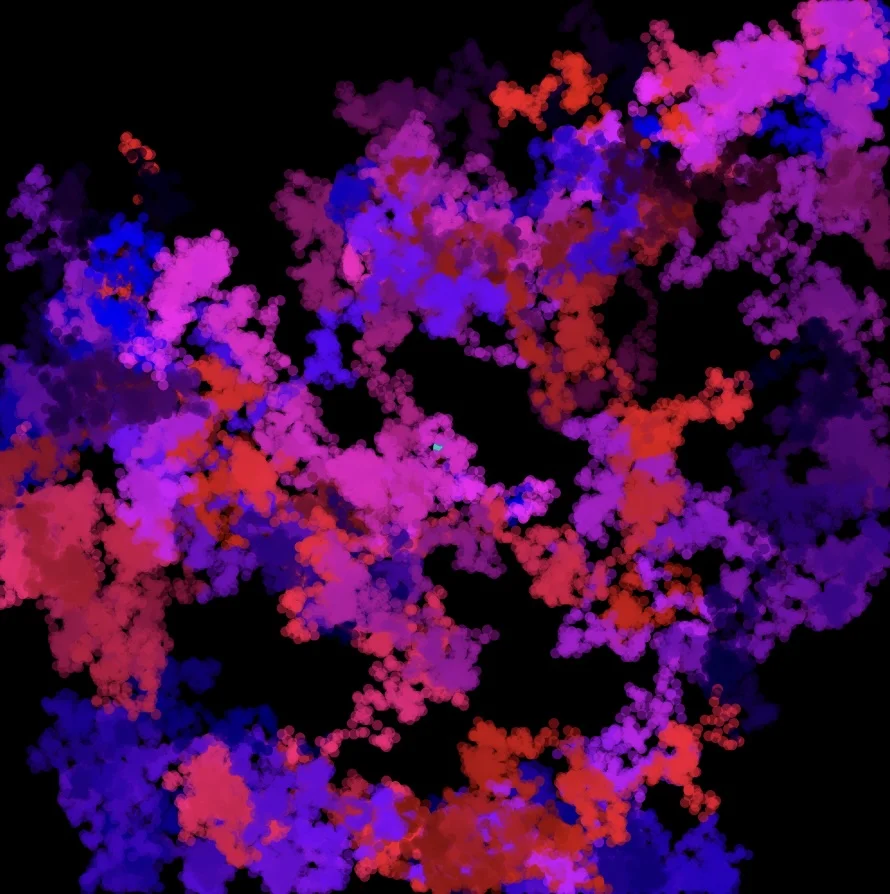

The image on the left is the result of a kind of 5-dimensional random walk in \((\mathbb Z)^2 \times [0,255]^3\) where \([0,255]^3\) is a representation of discrete RGB color space. More specifically, it the result of independent random walks on \((\mathbb Z)^2\) and \([0,255]^3\). For esthetic reasons, the random walk in the second factor holds the green component constant (\(g = 0\)). Consequently the random walk in the second component is effectively 2-dimensional. As a result, by Polya’s theorem, it is recurrent in both factors.

A random walk is one of the most fundamental objects in probability theory, with deep connections to harmonic analysis, potential theory, and statistical physics.

The Simple Random Walk on \(\mathbb{Z}\)

Let \((X_n)_{n \geq 1}\) be i.i.d. random variables with \(P(X_i = 1) = P(X_i = -1) = \frac{1}{2}\). The simple random walk is the partial sum process

\[ S_n = \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i, \quad S_0 = 0. \]

This is a martingale with respect to the natural filtration \(\mathcal{F}_n = \sigma(X_1, \ldots, X_n)\), since \(\mathbb{E}[S_{n+1} \mid \mathcal{F}_n] = S_n\).

Recurrence and Transience

A random walk is recurrent if it returns to the origin with probability 1, and transient otherwise. Pólya’s theorem (1921) gives a striking dimension-dependent dichotomy:

Theorem (Pólya). The simple random walk on \(\mathbb{Z}^d\) is recurrent if and only if \(d \leq 2\).

The proof hinges on computing the expected number of returns to the origin:

\[ \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \mathbf{1}_{\{S_n = 0\}}\right] = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} P(S_n = 0). \]

For the walk on \(\mathbb{Z}^d\), the return probability at time \(2n\) is

\[ P(S_{2n} = 0) = \left(\frac{1}{2d}\right)^{2n} \binom{2n}{n, n, \ldots} \sim \frac{c_d}{n^{d/2}} \]

by Stirling’s approximation. This sum converges iff \(d \geq 3\).

The Reflection Principle

A key combinatorial tool is the reflection principle. For paths from \((0,0)\) to \((n,k)\) that touch or cross zero, there’s a bijection with all paths from \((0,0)\) to \((n,-k-2)\) (for appropriate boundary conditions). This yields:

Ballot Problem. The probability that \(S_1, S_2, \ldots, S_n > 0\) given \(S_n = k > 0\) is \(k/n\).

Donsker’s Theorem (Functional CLT)

Define the rescaled process

\[ W^{(n)}(t) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} S_{\lfloor nt \rfloor}, \quad t \in [0,1]. \]

Theorem (Donsker). \(W^{(n)} \xrightarrow{d} W\) in \(C[0,1]\) equipped with the sup-norm topology, where \(W\) is standard Brownian motion.

This is the functional generalisation of the central limit theorem. The convergence is in distribution on the space of continuous functions, making it extremely powerful for deriving limit theorems about path functionals.

The Arcsine Laws

Three remarkable distributional identities, all involving the arcsine distribution with density \(\frac{1}{\pi\sqrt{x(1-x)}}\) on \((0,1)\):

- Last zero: \(\frac{1}{2n}\max\{k \leq 2n : S_k = 0\} \xrightarrow{d} \text{Arcsine}\)

- Occupation time: \(\frac{1}{2n}\sum_{k=1}^{2n} \mathbf{1}_{\{S_k > 0\}} \xrightarrow{d} \text{Arcsine}\)

- Time of maximum: The location of the maximum has the same limiting distribution.

These are counterintuitive—the walk spends most of its time on one side of zero rather than oscillating symmetrically.

Connection to Harmonic Functions

On \(\mathbb{Z}^d\), a function \(h\) is discrete harmonic if

\[ h(x) = \frac{1}{2d}\sum_{y \sim x} h(y) \]

where \(y \sim x\) means \(y\) is a neighbour of \(x\). Equivalently, \((h(S_n))\) is a martingale. This connects random walks to potential theory: the solution to the Dirichlet problem on a domain \(D\) with boundary values \(f\) is

\[ h(x) = \mathbb{E}_x[f(S_\tau)] \]

where \(\tau = \inf\{n : S_n \in \partial D\}\).

Generalisations

The theory extends naturally to random walks on groups (where the structure theory of Lie groups and amenability become relevant), random walks in random environments (RWRE), and self-avoiding walks (which connect to critical phenomena and conformal field theory in \(d=2\)).

Would you like me to expand on any of these directions—perhaps the martingale theory, the connection to Brownian motion, or random walks on groups?